Manifest Destiny

Not wanting to wake Carmella, Dillon sits up quietly and removes himself from bed. He locates his boots and pants, and carries them into the living room, where he dresses. He straps on his gun and grabs the day pack he often takes on trips up the canyon, tosses in a handful of protein bars, a couple of apples, and his old A harmonica. He fills his water bottle and puts it in the pouch on the side of the bag. Outside, the crickets chirp, and the bullfrogs sing their song of the night. They’re calling him.

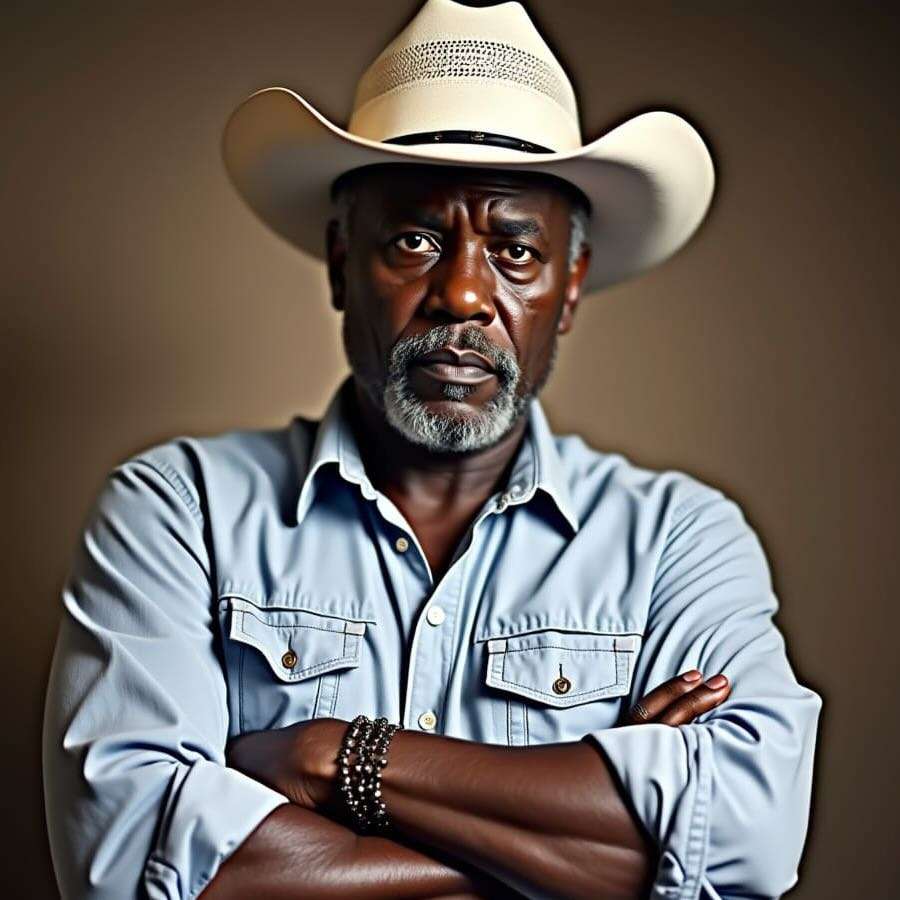

He grabs his wide-brimmed hat, which hangs by the door, and he enters the outdoors, softly closing the screen behind himself. For a moment, the crickets and frogs fall silent. The sky is clear, and the enormous stars seem too heavy for it to hold. The big gibbous moon, bloated like a corpse in the desert heat, lays impaled on a mountain peak. The little moon is yet to rise. For a microsecond, Dillon wonders if this place he’s immigrated to might actually be the land of the dead.

He takes the path down to the river toward the Sheriff’s Department stables. He can follow the Pecos up as far as Big Snake, then cut cross-country, maybe head up toward Crawford’s Hole or Witch’s Hat. He can check out the site of that massacre up at Newton’s Spring and be back by nightfall. Carmella will eat him alive if he misses the performance at The Uncertainty Principle tomorrow evening.

As he approaches the river, the night singers resume their music, and the musty smell of the water and its fecund life, its willows and honeysuckle and marsh grass and rotting plant matter, put him in mind of another place, somewhere, long ago. But the where and when are lost to him now.

Hearing his approach, the horses stomp the ground and neigh. He looks for Bettie, the new little sorrel mare Roxanne had broken in this spring. She’s a good, surefooted ride. He finds her in the third stall, next to Big Black. He strokes her nose, and she whinnies her approval.

“You want to go for a ride this evening, girl?” Dillon clips a lead rope onto her halter and opens the gate. He tethers her outside the tack room, saddles and bridles her, talking gently, occasionally feeding her a handful of grain.

He’d been opposed to the horses at first. For one thing, he’d never ridden a horse before. A greenhorn, Pedro called him. It had been part of Pedro’s fucking cowboy fantasy. But in the end, he had to admit that it was practical out here in this canyon country, with no roads and a shortage of motor vehicles. Now he won’t have it any other way. There’s nothing like a midnight ride on the desert chaparral, time slowed to a crawl, just a man and his horse and an endless horizon. Out there he can think about the stars and the vast distance between them. He can think about entropy and the Second Law of Thermodynamics. He can figure out the meaning of his life.

He finishes cinching the saddle and adjusts the bridle. He loops his day pack over the saddle horn and mounts. With a gentle snap of the reins, they’re moving east along the river trail through town, past the sleeping workers and their families, past the bridge to Order, past city hall, into the wilderness.

The well-worn trail up river to Big Snake holds no surprises. A single passing ore barge drifts by on the current, no doubt guided by autopilot as its tiny crew sleeps below deck. It’s at least an hour before dawn when Dillon reaches the first S in the river. Now well above the mountains, the two gibbous Moons provide some small quantity of light, but he’s hesitant to take the green mare overland at night in this treacherous terrain. He dismounts and ties her up on a grassy slope next to the water. Then he unsaddles her before searching for a comfortable spot to nap.

Another mile up river the lights of Blasón’s toll station illuminate the deep narrows on the upper S of the Big Snake. Pedro’s crew has built a barrier spanning the river, a massive gate which allows barges through for a price. Matt Dillon had decided long ago to ignore Blasón’s blatant thievery, but he knows Miglia or Cheng will eventually demand he control the situation. He isn’t looking forward to the confrontation, and he monitors it closely. Sharma reports to him daily, but, so far, nothing important has come over the wires, just an occasional encrypted message, usually outbound.

His thoughts turn to Jolene Cheng and whatever devil’s bargain she’s offered Blasón. It’s only a matter of time before it blows up in their faces. Miglia is no fool. The thing is, it put Dillon smack in the middle. Cheng’s his immediate superior. In the end he still has to answer to Dick Miglia.

He finally finds a soft sandy place near the river and tosses down the saddle blanket. The night’s still warm, nearly 24C as far as Dillon can figure. The temperature hasn’t dropped below twenty for a couple of weeks now, but it isn’t as sweltering as a few days ago. A person can sleep in this weather.

For a while, he plays his blues harmonica, releasing its lonely cries into the empty night. When the weariness finally catches up to him, he lays down his head and closes his eyes.

When Dillon wakes, the sun has risen, casting long red shadows across the desert landscape. At the river, he cups a handful of water and splashes it on his face. Then he takes another before saddling up Bettie and mounting. He rides northeast, away from the river, toward the big black cinder cone called Witch’s Hat. About ten kilometers north of Witch’s Hat lies Crawford’s Hole, an old impact crater. Between the two, the oasis of Newton’s Spring harbors the little mining town of Manifest Destiny.

Dillon doesn’t know what he’ll find there. The travelers who reported the massacre had buried the dead. There’d not likely be much evidence left, but he needs to see the scene just the same. Maybe he can find a clue about the killers—where they’d come from, where they’d gone. That’s the crazy thing. It’s been ten years since they established the town of Law and Order. Miners had crawled all over this country, and not one has ever found a native village, seen only fleeting silhouettes on the horizon, or the aftermath of their brutality. A few survivors reported “Indians” on horseback, but they’d never found the bodies of marauders. The dead, it seems, just vanished.

It’s nearly noon when Dillon skirts Witch’s Hat. In the distance he sees the green poplar trees which sustain themselves on the artesian waters of Newton’s Spring. A red-tailed hawk circles lazily in the sky, then seeing a possible meal on the ground, tucks his wings back and falls from the heavens in a swift, graceful dive. Dillon follows a shallow arroyo down the hill toward town. The sun’s now becoming unbearably hot and Bettie’s worked up a sweat. She’ll need water soon. Dillon pulls an apple out of his daypack and eats a few bites, then he gives the remainder to his horse. He strokes the length of her neck. “We’re almost there, girl. Hang on.”

Dillon can now make out a few trailers, their metallic shells reflecting the bright sunlight. A dust devil crosses the dirt road between them, stirring up some discarded cardboard and a soft drink cup, before moving off to the west. As he approaches the broken down buildings, it seems as though the town had been deserted decades ago.

Dillon locates the spring bubbling from the ground and allows the mare to drink her fill before tethering her to graze. He wipes the sweat from beneath his hat lining, then walks toward the center of town. More trailers and ramshackle houses in need of paint, a small grocery store with a faded Coca Cola sign and a gasoline pump out front. Not much else.

He imagines the miners, cold beer in their hands, sitting out front of the store, talking about work and telling bawdy jokes, their wives hanging the laundry out on the lines behind the trailers, kids running down the dirt road through town, kicking up dust storms. He could almost taste the dust as it swirls around him. He wonders if there might be a cold drink in some cooler still powered by the solar array on the rooftop. He decides it would probably be sacrilegious to steal from the dead. Yet the sun is hot, the kind of hot you don’t want to be caught up in without plenty of liquid.

Dillon turns back to the springs. While the buildings of Manifest Destiny cluster near the bubbling water, the oasis of trees and grass stretch for a kilometer in a long green line before the arid desert earth reclaims the life-giving liquid. He sees, at the far end of the green swath, a rock formation jutting from the sand. The sort of place he imagines a raiding party might hide and wait.

He satiates himself and refills his water bottle. Then he follows the trickling stream toward the outcrop. Dillon walks slowly, scouring the earth for clues, until about halfway down the long stand, something moves in a clump of willows, and he reaches instinctively for his Colt. He freezes, listening, watching for movement until he decides his imagination has conjured a phantom. But he moves more cautiously now, attempting to engage all his senses. It seems unlikely that the band that killed those people is still around, but you never know who else might be. Newton’s Spring is an oasis in the desert, a precious water source for thirsty travelers.

He sees nothing on his walk that indicates the recent massacre. No misfired arrows, no dead natives. The strange outcropping, however, immediately draws his interest. From a distance, it seems like weather-rounded sandstone. But close up, it’s definitely something else.

Then he understands—adobe. This is the ruins of a rammed-earth wall, perhaps centuries old. As he encircles it, he decides it had once been some sort of dwelling. A search of the surroundings turns up no obvious signs, only the bare footprints of children. He steps over the rubble of a crumbled archway. Inside the structure, he finds some plastic soldiers and other evidence that the town’s children played here. He imagines them holding their tiny toys, as he’d done in his own childhood, aiming at one another. “Bang, you’re dead,” crying and falling, mortally wounded, child and toy melded into one.

A slight dizziness overcomes him. Dillon wipes the sweat from his forehead and sits unsteadily on a low stone ledge, closing his eyes for a moment. When he opens them again, a tall, thin reed of a man is sitting across the room from him. The man wears clothes similar to Dillon’s own, denim and light cotton. He seems vaguely familiar.

“Hello, Matthew,” he says. “Welcome to my home.”

Startled, Dillon slides his hand to his revolver. “Where the hell did you come from? Do I know you from somewhere?”

“Perhaps we’ve met somewhere. Perhaps…” The man lets his words trail off.

“How do you know my name?”

“You told me, of course. Just now.”

That’s funny, Dillon can’t remember speaking. “And you are?”

“Oh, you probably couldn’t pronounce it. It isn’t reproducible with your apparatus.” The man indicates his throat. “You can call me Ben, if you like.”

“You say this is your home, Ben? You mean Manifest Destiny?”

“No, I mean this dwelling, Matt.”

“You’re nutty as a fruitcake, man. I’ve just been all over here. Nobody’s lived in this place for centuries.” There’d been no sign of an adult here, human or otherwise. “Where are your footprints, Ben?”

Ben turns his gaze to the ground, then back to Dillon, puzzlement on his face. “That is odd,” he says. But there’s a twinkle in his eye.

Yes, thinks Dillon, extremely odd. “Do you know what happened to those people, Ben?”

“I tried my best to warn them, Matt. I enjoyed the little ones running around the house. It is so sad.”

“Who killed them? Did you kill them?”

“Their deaths were self-inflicted, I’m afraid.”

Dillon’s fingers tighten their grip on his gun. “What do you mean, man? They were massacred with hatchets and arrows.”

“Yes, I know.” Ben’s looking off into the distance now. A single tear runs down his face.

“What makes you think they killed themselves?”

“Because…” Ben says, his voice breaking, “because it happened to my family, too. We had no choice, you see, but to kill ourselves.”

Dillon’s head reels. Is he hallucinating? It doesn’t seem like a hallucination.

“How does a man produce an arrow from thin air and then pierce his own heart with it?”

“You should consult the Memories about that, Matt.”

Dillon feels another wave of dizziness and reaches for his water bottle. The sun has shifted slightly, its glare obscuring his vision, and he thinks he can see a sort of house behind that curtain of light, a warm, beautiful lived-in home, its furnishings rich and unearthly, and when he looks back at Ben, he sees something, something not human at all, fading in the shimmering photon waves.

Manifest Destiny

- A Short Story

- by Duane Poncy & Patricia J McLean

Excerpted from the novel, Degrees of Freedom, part two of The Sweetland Quartet. Originally published in the Central Oregon Writers Guild 2024 Anthology.